- https://PayPal.Me/lukeisback

"Luke Ford reports all of the 'juicy' quotes, and has been doing it for years." (Marc B. Shapiro)

"This guy knows all the gossip, the ins and outs, the lashon hara of the Orthodox world. He’s an [expert] in... all the inner workings of the Orthodox world." (Rabbi Aaron Rakeffet-Rothkoff)"This generation's Hillel." (Nathan Cofnas)

Why Is The Elite Media Singing From The Same Hymnal About The Trump-Putin Summit? II (8-17-25)

Posted in America

Comments Off on Why Is The Elite Media Singing From The Same Hymnal About The Trump-Putin Summit? II (8-17-25)

Ira Israel: Could Enlightenment Mean Accepting Our Own Insignificance?

I’ve spent my life chasing distinction instead of connection. When I change this habit and spend more energy on connection instead of attention, I not only increase my happiness, I also become more effective.

We can’t always win in the attention economy but we can all become more effective.

What annoys me about pundits is that they primarily promote themselves rather than the truth.

The truth is that we and they are insignificant (except to a tiny number of people connected to us such as family and friends).

If I died today, a dozen people would be devastated and a few hundred people would be sad.

Ira Israel is on to something here:

It may sound paradoxical but what if the path to enlightenment begins with accepting our own insignificance? What if the drive to be “somebody” is what fuels our anxiety and depression?

As a therapist, I often see patients struggling under the weight of needing to feel significant. In helping them, I have found surprising common ground between three different traditions: the Buddhist concept of sunyata, philosopher Jean‑Paul Sartre’s idea of nothingness, and psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan’s notion of subjective destitution. Each challenges our attachment to self‑importance, not to erase the self but to free it. And far from espousing nihilism, each theory outlines a path towards freedom and authenticity.

We live in a culture that rewards visibility — likes, follows, and polished personal “brands” that we create mostly for social media. Most of us are conditioned to equate attention with worth, but this hunger for admiration often breeds alienation, resentment, frustration, jealousy, and disappointment — from others, and even from ourselves. What if well‑being doesn’t come from building shinier facades, but from loosening our holds on trying to be significant?

…The self is not fixed or permanent.

Emptiness or lack is not a defect; it’s the starting point for freedom.

Clinging to self‑importance fuels suffering and alienation.

Letting go invites more responsible, authentic engagement with life.

Rejecting self‑importance doesn’t mean drifting into passivity or cynicism. These ideas can help us redirect our energy toward genuine connection and contribution:

Serve compassionately: Let meaning come from helping others, not from seeking validation.

Live your values quietly: Integrity matters more than applause.

Build inclusive communities: Welcome people for who they are, not what they achieve.

Support larger causes: Invest in the well‑being of the planet and others.

Mentor without ownership: Share knowledge freely, without needing credit.

Create as an offering: Let art or innovation enrich life, not your résumé.

Listen deeply: Hear others without rushing to center yourself.

Be present: Release preoccupation with recognition; focus on the moment at hand.

Practice spontaneous kindness: Give without calculation.

Stay vulnerable: Honest sharing fosters real connection.

Posted in Pundits

Comments Off on Ira Israel: Could Enlightenment Mean Accepting Our Own Insignificance?

The Prestige Economy

The more prestigious your job (such as an Ivy League professor or network news anchor), the more vulnerable you are to cancellation for crime think.

The professor and the elite journalist primarily work in a prestige economy while the businessman and the athlete typically work in a merit economy.

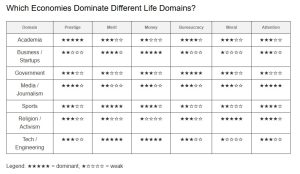

How many economies are there and which ones dominate your life?

ChatGPT: 1. Prestige economy (status-based)

What matters: recognition, reputation, who praises you, where you’re published, who you’re seen with.

Domains: academia, journalism, arts, fashion, politics, social media.

Logic: value is conferred by peers or gatekeepers. You succeed by being recognized as “important,” not necessarily by measurable output.

Downside: herd effects, echo chambers, fear of deviating from consensus.

2. Merit economy (performance-based)

What matters: measurable outcomes, skill, output, or results.

Domains: engineering, some parts of business, sports, surgery.

Logic: value comes from demonstrated ability or productivity — you win the race, you design the bridge that stands.

Downside: merit measures can get gamed; not all “merit” is measurable.

3. Money economy (market-based)

What matters: purchasing power, price signals, capital.

Domains: commerce, labor markets, investment.

Logic: value is set by supply and demand; anyone who can pay can access.

Downside: inequalities compound, wealth isn’t always aligned with wisdom or talent.

4. Bureaucratic economy (rule-based)

What matters: compliance, seniority, credentials, ticking the right boxes.

Domains: government, big corporations, military, HR departments.

Logic: you advance by following the rules, meeting formal criteria, or lasting long enough in the hierarchy.

Downside: sclerosis, box-ticking over substance.

5. Moral economy (norm-based)

What matters: virtue, altruism, adherence to shared values.

Domains: religion, activism, community life.

Logic: esteem and trust are granted for being “good” or “selfless.”

Downside: moral signaling can substitute for effectiveness; purity spirals.

6. Attention economy (visibility-based)

What matters: eyeballs, clicks, followers, virality.

Domains: social media, entertainment, politics.

Logic: value flows to whoever can grab and hold attention, regardless of truth or depth.

Downside: incentivizes outrage, spectacle, simplicity over nuance.

In real life, these overlap. A professor is judged partly on merit (quality of research), partly on prestige (journal placement, who cites them), partly on bureaucracy (tenure rules), and increasingly on attention (social media presence).

Legend: ★★★★★ = dominant, ★☆☆☆☆ = weak

This lets you see at a glance:

Academia = prestige + bureaucracy.

Media = attention + prestige.

Government = bureaucracy + prestige.

Business = money + merit.

Sports = pure merit, but layered with money and attention.

Religion/activism = moral + attention economies.

Tech/engineering = merit + money, though prestige is creeping in (e.g. conference buzz, VC signaling).

How Economies Interact and Distort Each Other

Prestige vs Merit

- Distortion: Prestige can overshadow real ability. A Harvard degree may be valued more than raw skill.

- Example: In academia, citation counts and institutional prestige often count more than the actual content of research.

Prestige vs Money

- Distortion: Money can buy prestige (endowed chairs, naming rights) while prestige can inflate financial value (celebrity endorsements).

- Example: Universities admit big donors’ kids regardless of academic merit.

Merit vs Bureaucracy

- Distortion: Bureaucratic rules can block recognition of actual talent, while “meritocratic exams” can be gamed.

- Example: In government jobs, civil service rules sometimes promote time-in-grade over performance.

Attention vs Merit

- Distortion: Viral fame can eclipse actual competence.

- Example: Influencers with millions of followers get lucrative deals while more talented but unknown creators get ignored.

Moral vs Money

- Distortion: Moral appeals can be monetized, turning causes into brands. Conversely, financial backers shape which causes gain traction.

- Example: “Green” or “woke” consumerism where virtue is sold as a premium lifestyle choice.

Prestige vs Attention

- Distortion: High-prestige actors chase attention, diluting their credibility; attention-seekers borrow prestige through association.

- Example: Scientists on Twitter simplify or exaggerate findings to gain followers, which can undermine long-term trust.

Key Takeaway

Most domains run on a mix of these economies. But when one dominates—especially attention or money—it tends to distort the others. That’s why elite media, academia, and politics so often sound uniform: they are trapped in overlapping prestige–attention–bureaucracy loops that leave little room for pure merit or truth-seeking.

Prestige Economies Driving Elite Media Behavior

Biden’s Cognitive Decline Denial

- Prestige Economy: Elite outlets like NYT and Washington Post prize their credibility and elite standing. Admitting Biden’s decline early would risk sounding like right-wing talking points, which would lower their standing in the prestige hierarchy of journalism.

- Attention Economy: Stories affirming Biden’s competence were rewarded with clicks from their loyal base, while dissenting voices risked alienating that audience.

- Bureaucratic Economy: Newsrooms have internal norms—editors, standards desks—that function like bureaucracies. Deviating from the “he’s fine” line meant career risk inside the institution.

- Result: Groupthink. A uniform narrative of “Biden is sharp” prevailed until obvious signs made denial impossible (Politico eventually broke ranks).

Trump’s Trade Policy Derision

- Prestige Economy: Economists in places like the Brookings Institution and CBO had long treated free trade as settled orthodoxy. Journalists mirrored that prestige consensus rather than re-examining assumptions.

- Merit Economy: Actual outcomes (tariff revenue, renegotiated trade deals, resilience arguments) were ignored because they conflicted with the prestige line.

- Attention Economy: “Trump the fool on trade” stories drove traffic, fitting reader expectations. Nuanced analysis (“tariffs could raise $3 trillion in revenue over a decade” – CBO) was buried.

- Result: Uniform ridicule—until later, when outcomes complicated the narrative and some humility began creeping in (FT analysis).

Takeaway

Neither case is about truth alone. The uniformity comes from overlapping economies: prestige (status within the profession), attention (traffic and audience loyalty), and bureaucracy (institutional norms). When those dominate, reality gets filtered until it can no longer be ignored.

Russiagate: How the Prestige Economy Produced a Single Story

| Economy at work | What it looked like in coverage | Receipts |

|---|---|---|

| Closure | Early boundary-setting: skepticism about “collusion” framed as unserious or partisan; dissenters treated as outside the pale. | Mueller Report (redacted, WaPo annotated) (no established conspiracy); DOJ IG FISA review (17 significant errors/omissions); Durham Report (2023) (procedural/analytic failures); 2018 Pulitzer to NYT/WaPo for Russia-coverage. |

| Prestige | High-status outlets and security-state alumni defined the respectable view; others echoed to signal professionalism. | Pulitzer Board award announcement (2018); Board later stood by the award (2022). |

| Anti-neutrality | Neutral, wait-and-see reporting often read as “carrying water.” Safe moral stance: assume the worst about Trump/Putin links. | Mueller Vol. I (DOJ) on interference vs. conspiracy findings; Horowitz press PDF (Dec 2019) summarizing FISA problems. |

| Bureaucracy | Newsroom norms and sourcing pipelines (intel, DOJ, FBI alumni) rewarded sticking to the herd; editors risk-averse to contrarian frames. | House Intel letter on IG findings (details errors/omissions); House hearing on Durham (2023) (competing interpretations). |

| Attention | Incentives favored dramatic “Watergate-scale” arcs; reversals or nuance underperformed compared with scandal-forward framing. | Mueller report archive (public interest spikes); Media debate over revoking awards: Axios (2019). |

Turner-style takeaway

- Closure came first (declare the narrative settled), then prestige enforced it (who is credible to say what), while bureaucratic newsroom habits and the attention economy kept the arc intact.

- When later documents complicated the original frame (Mueller non-establishment of conspiracy; IG FISA errors; Durham’s criticisms), the system largely reframed rather than retracted—preserving credibility capital.

Quick links (primary docs)

- Mueller Report (Vol. I, DOJ) • Mueller Report (Vol. II, DOJ)

- DOJ IG: Crossfire Hurricane & FISA (Dec 2019)

- Durham Report (May 2023) • Declassified Durham Annex (2025)

- Pulitzer 2018: NYT/WaPo (National Reporting) • Board statement standing by award (2022)

In the positivist picture, life (especially intellectual life) runs like a merit economy: each discovery is a brick in the wall of cumulative knowledge, neat and impersonal. That’s what people like Comte or logical positivists hoped for — knowledge as an ever-growing model that nobody can really dispute once the facts are in.

But in practice, as Turner emphasizes, much of life — not just science but culture, politics, journalism — runs like a prestige economy. Knowledge isn’t simply added up; it’s negotiated, policed, and stabilized by people who hold authority, credibility, or symbolic capital. The “conversations” decide what counts as knowledge and what doesn’t.

So how much of life operates like this?

Academia: Almost entirely. Journals, tenure committees, funding agencies, and disciplinary boundaries decide what is knowledge. Prestige hierarchies matter more than raw merit.

Media and public discourse: Heavily. A story is not true or false in the abstract; it’s “true” if The New York Times or The Washington Post says so, and untrue if it comes from “fringe” or “conspiracy” outlets.

Law and politics: Same. Courts and legislative bodies are “conversation arenas” where closure happens not because the facts are final, but because a ruling or statute gives a definition the force of authority.

Everyday life: Even at a smaller scale, reputations and cliques determine who is believed in a workplace, a family, or a church.

Where does the merit economy still operate?

In narrow technical domains where feedback from reality is brutal and immediate — like engineering, surgery, or competitive sports. If the bridge collapses, no amount of prestige talk can save you.

Even then, prestige can shape who gets to build the bridge in the first place, or whose failure gets excused.

So the blunt answer: most of life is prestige economy, with pockets of merit economy wherever the world forces brutal feedback.

Posted in Economics

Comments Off on The Prestige Economy

The Engineered Chinese State Vs Lawyerly America

The Financial Times writes: “China is run as an engineering state that excels at construction while the US has become a lawyerly society that favours obstruction. By 2020 all nine members of the Chinese Politburo’s standing committee had trained as engineers. By contrast, the US has turned into a “government of the lawyers, by the lawyers and for the lawyers.””

Amazon says about this new book, Breakneck: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future:

A riveting, firsthand investigation of China’s seismic progress, its human costs, and what it means for America.

For close to a decade, technology analyst Dan Wang―“a gifted observer of contemporary China” (Ross Douthat)―has been living through the country’s astonishing, messy progress. China’s towering bridges, gleaming railways, and sprawling factories have improved economic outcomes in record time. But rapid change has also sent ripples of pain throughout the society. This reality―political repression and astonishing growth―is not a paradox, but rather a feature of China’s engineering mindset.

In Breakneck, Wang blends political, economic, and philosophical analysis with reportage to reveal a provocative new framework for understanding China―one that helps us see America more clearly, too. While China is an engineering state, relentlessly pursuing megaprojects, the United States has stalled. America has transformed into a lawyerly society, reflexively blocking everything, good and bad

Blending razor-sharp analysis with immersive storytelling, Wang offers a gripping portrait of a nation in flux. Breakneck traverses metropolises like Shanghai, Chongqing, and Shenzhen, where the engineering state has created not only dazzling infrastructure but also a sense of optimism. The book also exposes the downsides of social engineering, including the surveillance of ethnic minorities, political suppression, and the traumas of the one-child policy and zero-Covid.

In an era of animosity and mistrust, Wang unmasks the shocking similarities between the United States and China. Breakneck reveals how each country points toward a better path for the other: Chinese citizens would be better off if their government could learn to value individual liberties, while Americans would be better off if their government could learn to embrace engineering―and to produce better outcomes for the many, not just the few.

Posted in China

Comments Off on The Engineered Chinese State Vs Lawyerly America

Cognitive Science and the Social: A Primer

ChatGPT gave me the juiciest bits from this 2018 book:

Reductionism critique – Turner jabs at the enthusiasm for explaining social life in purely cognitive/neural terms, noting how easily “cognitive” talk reifies the brain into an autonomous agent. He hints that this is more fashion than science.

Neural metaphors as ideology – He argues that borrowing concepts like “neural networks” to describe society smuggles in an ideological agenda: it makes social order look natural and mechanistic, masking politics.

Cognitive science’s hidden philosophy – He exposes that many “scientific” claims are actually disguised philosophical assumptions (about intentionality, meaning, rationality). This is a classic Turner move: showing that epistemic closure hides under the mantle of science.

Suspicion of grand synthesis – He hints that cognitive science’s dream of unifying brain, mind, and society is a secular theology — a replacement myth for older religious narratives of unity.

Agency vs. mechanism – He notes that if we take the mechanistic view too literally, there’s no room left for responsibility or meaning. The juicy aside here is: cognitive science undermines the very categories (choice, accountability) that social order requires.

Science wars echoes – He connects critiques of “creation science” and “sociobiology” with how cognitive science papers over its own ideological biases. His quiet subtext: today’s “neutral science” is tomorrow’s dogma.

Recurrent warning – He suggests that when science claims to be final on social explanation, it’s usually serving a political need—whether it’s legitimizing AI, governance, or surveillance. That’s one of his sharpest and most controversial insights in this book.

Anti-reification again: Turner keeps hammering that “cognition” isn’t a black box or a ghost in the machine—it’s a set of practices, habits, and distributed processes. He drops little grenades at cognitive scientists who talk as if “the mind” were a self-contained entity.

Social learning as scaffolding: He emphasizes that much of what we call “cognition” is really embedded in external props (language, institutions, tools). That means social order is as much about maintaining scaffolds as about training minds.

Attacks on “rules” talk: He points out that many theories (from Chomsky’s grammar to Searle’s social ontology) smuggle in “rule-following” as if rules exist somewhere Platonic. Turner insists this is a mistake: rules only exist in the practices that reproduce them.

Memory as externalized: He highlights that much of human memory is outsourced—books, notes, shared practices—undermining the neat boundaries between “individual” and “collective” cognition.

Implication for social science: If cognition is scaffolded and external, then social facts are not metaphysical things “out there.” They are precarious and contingent networks of habits and artifacts—exactly the kind of anti-reification line Turner always presses.

Juicy aside: He quietly notes that when people call things like race, gender, or “society” themselves cognitive categories, they’re usually reifying them, making them sound more real than they are. In his framing, they’re better seen as heuristic constructs tied to practices.

In Cognitive Science and the Social: A Primer, Turner takes up sociobiology and evolutionary psychology as part of his broader critique of reified explanations of human behavior. A few highlights:

Suspicion of “just-so stories”: He points out that sociobiological accounts often rely on speculative evolutionary narratives—explaining current behaviors as adaptive without strong evidence. This, for Turner, is a form of reification: treating contingent cultural patterns as if they were hardwired biological facts.

Reductionism problem: He stresses that reducing complex social phenomena to biology misses the scaffolding—language, institutions, external memory, practices—that actually sustain them. Sociobiology tends to act as if these supports were secondary rather than constitutive.

Overlap with cognitive scaffolding: He notes that many behaviors attributed to “genes” or “evolutionary imperatives” can be better explained by distributed cognitive systems: the way habits, artifacts, and practices organize behavior without invoking hidden biological drives.

Politics of expertise angle: He also hints (consistent with his other books) that sociobiology gained traction partly because it provides a “scientific” gloss on social order—an authority claim. That makes it an instance of expertise being used to close down debate rather than open it up.

Anti-essentialism: He repeatedly warns against treating categories like “altruism,” “aggression,” or “intelligence” as natural kinds. Sociobiology tends to assume such essences exist, whereas Turner insists they’re contextual and socially scaffolded.

So in short: Turner doesn’t dismiss sociobiology out of hand—he treats it as an interesting explanatory impulse—but he consistently undercuts its explanatory power by showing how it reifies, skips over scaffolds, and smuggles ideology in the name of biology.

Posted in Stephen Turner

Comments Off on Cognitive Science and the Social: A Primer